Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl. The Definitive Edition. Edited by Otto H. Frank and Mirjam Pressler. Translated by Susan Massotty. (New York: Everyman’s Library/Alfred A. Knopf, 2010).

“The best remedy for those who are frightened, lonely or unhappy,” Anne Frank tells us in her diary, “is to go outside, somewhere they can be alone, alone with the sky, nature and God” (p. 163). To retrace the words of Anne’s sentence is to travel a path from lonely to alone and arrive nonetheless healed. It’s one of the many striking moments of therapeutic longing that can be found in The Diary. And heartbreaking too, of course — for when Anne finally did manage to go outside, after more than two years of confinement, she was decidedly not alone. In fact, from the time of her arrest on August 4, 1944 to the time of her death from typhus and starvation in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp sometime in the winter of 1944–45, Anne Frank was probably never completely alone for one single moment. Nor even in death did Anne manage to fulfill the remedy that she had prescribed for herself one Wednesday morning in an Amsterdam attic: After Anne died, her body was dumped in a mass grave where even her unprivate bones could decay without particularity or uniqueness.

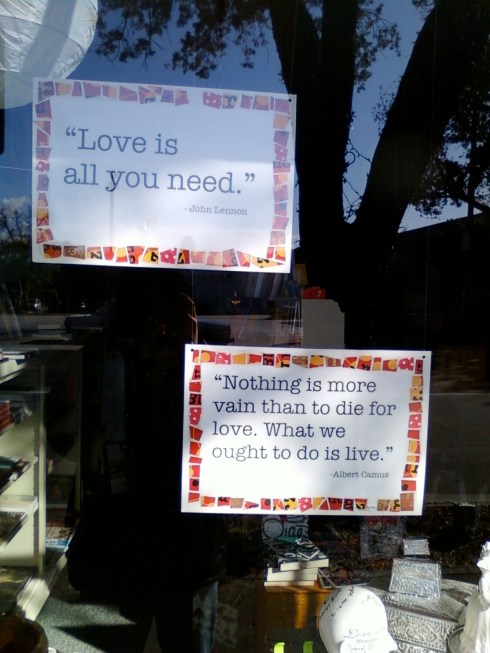

The phrase “I don’t want to die alone” has become almost a cliché in our culture. The announcement likely carries with it memories of darkly humorous conversations among friends (“Whenever I take that horse pill, I imagine choking and dying alone” — or a million similar riffs). The television show Six Feet Under made something of a career out of this type of narrative. Every episode began with an ironic way to die — not always alone — but versions of dying alone certainly played a principal role in the show’s opening teasers. And although we live surrounded by people — millions more every year — the demon of isolation remains vivid in our imaginations. The more we invent ways to “connect” — think Twitter and Facebook of course, but think also of meetup.com and “spontaneous crowd” events — the more stubborn isolation’s specter seems to prove. Anne’s distinction between lonely and alone is a distinction that has a particular resonance in our time: The more we touch-pad ourselves together every second of the day the more we can feel the oppositional quality of the two words. Perhaps young Mark Zuckerberg constructed a large chunk of the platform upon which we now live out our lives, but I’d give it all back in a second if Mr. Social Network could just program the monster of loneliness into extinction.

And to read The Diary is also to understand a kind of privilege inherent in “I don’t want to die alone”–type announcements. We live our lives, most of us at least, with the blessings of aloneness: we can walk alone; we can think alone; we can read and write alone. And then we have the privilege of being able to end this privacy and seek the pleasures of company. To be fully human is to enjoy the differences between public and private spaces — between social modes and solitary ones. Anne’s confinement makes her pine not for the girl she once was, who had “five admirers on every street corner” (p. 171), but rather for the pleasures of being alone in an open space, for a solitary walk under the gray skies of Holland.

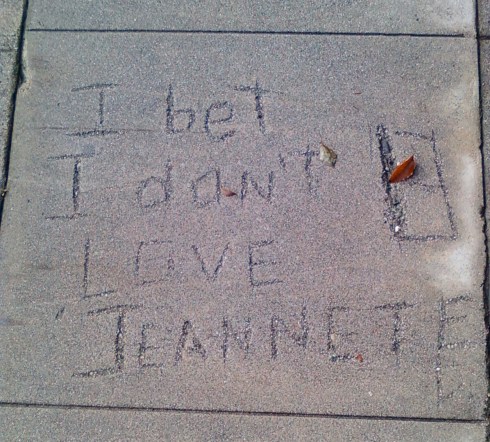

Last Sunday evening I walked from my apartment, where I live alone, to a housewarming party that some friends of mine were hosting. A completely unremarkable journey and yet to walk even a moderate distance (three miles in this case) is to pass through an evocative gallery of human activity. Unlike a car trip, a long walk gives us time to stitch together the variety of spaces through which we travel. (Train trips are often romanticized using similar reasoning. The late Tony Judt, for example, wrote beautifully and urgently about the glories of rail travel.)

And what of my unremarkable trip? What particularities did I notice as I moved through the world in the course of an hour’s walk? About ten minutes into my walk, I stopped at a home-furnishings store to buy a gift card for the new homeowners. The store’s perfumed candle-smells lingered in my nose long after I had exited. Later, I passed two different dance studios. In the first, a ball-room class — music-less for me as I watched for a moment from the street. Behind the glass wall, a dozen or so older couples waltzing, or almost waltzing, or merely linked in a vaguely dance-like embrace, smiling and moving their knees slightly, the actual motion of the dance, I’d like to think, happening perfectly somewhere in their imaginations. In the second studio, a girl in black tights, alone. A portable, 80s-style boom box was balanced on a folding metal chair. The girl pushed a button on the tape deck and started moving. She danced awkwardly but with a focused determination.

Earlier in my walk, I had passed a woman whom I had seen many times before: a short, heavy, Black woman with an abnormally childlike, squeaky voice. She seemed to own only one outfit: purple nursing scrubs. She’d ask me for change and I would seldom give it — for no good reason other than I was put off by her manner, the oddity of her voice. But on this Sunday evening, she stood — almost frozen really, an empty Styrofoam coffee cup in her hands — outside a Mexican restaurant. She was dressed in jeans and a blue top — her nursing costume had been replaced. The woman’s back was to me and I didn’t hear her voice as I walked by.

I was the first to arrive at the party — a disappointment, as I had managed, during the span of my journey, a daydream about my solitary walk being broken by the comforting noises of a party in full swing. Nevertheless the new house was beautiful and eventually filled up with friends and strangers and children, the younger children running around with stuffed pandas, while the slightly older ones argued about Phineas and Ferb and threatened to investigate patches of the new house from which they had been prohibited. What more could a man who lives alone desire? By the end, I sat exhausted on the cavernous white sofa and contented myself with blood-orange lemonade and the feeling that, because I had walked there, my own residence was now, in some perhaps insignificant but nevertheless organic way, connected to Jake and Sam’s new house.

What Anne longed for at the end of her lonely–alone sentence was, quite simply, absolutely everything: “the sky, nature and God.” There’s not much to imagine that isn’t under the aegis of one of those three categories. In syntactical terms, this everything becomes the way Anne balances the three words of desperation that occupy her first clause: “frightened, lonely, or unhappy.” After nearly 16 months of confinement with seven other people, the desire for a solitary observation of the world’s variety had taken root in Anne’s imagination. And more than 60 years after that confinement, the statement of a frustrated, energetic, petty, and thoughtful teenage girl can still be read as a powerful affirmation of the world that awaits us, for better and for worse, just beyond our doorsteps.